The diversification of a logistics fleet– what does it mean for a manager?

The diversification of a logistics fleet– what does it mean for a manager?

Authored by: Lukas Marthaler & Lorena Axinte

Last mile deliveries have been significantly uprooted in recent years with the rise of online shopping, high customer demands, and significant changes in urban planning policies. Whereas customers expect same-day delivery, cities are transitioning towards decarbonisation, introducing traffic calming measures such as Low Environmental Zones (LEZ), 30 km/h zones, time zones and prescribed loading and unloading zones. These trends require significant adaptation for logistics operators, who are further pressured by limited and expensive parking space in cities, as well as increasing vehicle insurance costs.

This creates a competitive environment for logistics operators, who must diversify their last-mile delivery fleet to stay ahead. Thus, a shift is taking place – from standard logistics models with a limited range of delivery vehicles towards a diversified fleet – leading to significant changes in the daily operations and the roles that both managers and other members of staff must perform. Nonetheless, the logistics sector is extremely diverse (e.g., food delivery vs. warehouse operations), and diversification can take many shapes. In this sense, diversity can mean using different types of vehicles and technologies, sharing vehicles (between companies or between different operations within a company), or not having a vehicle at all.

Growing flexibility is needed to adapt and comply with the ongoing changes in cities. This requires fleet managers to rethink their logistic operations, involving complex strategical, tactical, and operational changes in finances, organisation, logistics and commerce.

Challenges for managing a diversified logistics fleet

For a successful transition towards decarbonisation, fleet managers should start by asking themselves the following questions:

1. What does my logistics environment look like now, and what will it look like in the next 10 years?

2. What is the future fleet we need and what do we need it for?

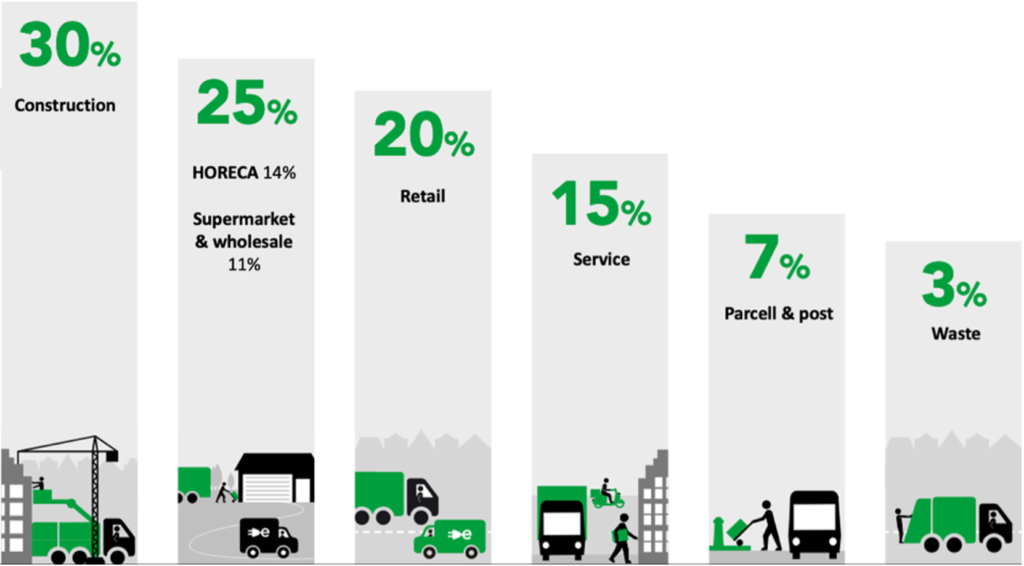

The answer to the first question is highly dependent on the local context and the changes which public authorities might make. The unpredictability of urban planning measures is a main concern for fleet managers, as adaptation might take significant amounts of time. However, each manager must also reflect on the second question to find the best match between operational needs, vehicles and technologies, and local context. Challenges differ greatly between the major logistics streams of urban freight (parcels and express, general cargo and retail, temperature-controlled logistics, waste, facility/service trips, construction). Their respective customers and delivery contents require different cargo bodies, delivery time windows and locations to be reached. Simply put, a supplier of constructions material for a site in the city’s outskirts will experience different logistical challenges compared to a fish supplier for restaurants in a pedestrianised historical city centre. Figure 1 uses the example of Amsterdam to give an indication towards the size of urban logistic streams, counted by the percentage of Light Commercial Vehicles (LCVs) per logistics stream compared to the total registered LCVs.

Source: Amsterdam Autoluw Agenda, 2020

Using interviews with key stakeholders and results of previous research (e.g., Go Electric – AUAS), we look at some general issues posed by fleet diversification for managers of all logistics segments, deep diving into practical lessons learned from BPost throughout their journey. BPost is the company responsible for Belgian national and international post delivery, that has shown to be an active innovator in their last-mile delivery fleet.

Choice of vehicles, loading units and technologies

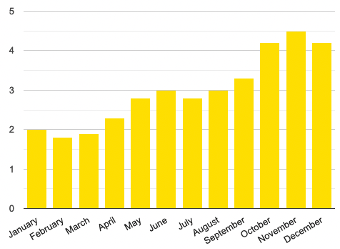

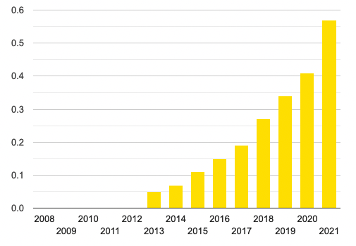

Whereas most of the current last-mile delivery fleets in Europe still include diesel vans, there is a significant upwards trend in the uptake of electric Light Commercial Vehicles (e-LCVs) (see figures 2 and 3). Besides e-LCVs, examples of ongoing R&D and diversification in last-mile fleets include the following vehicles and technologies:

- Cargo bikes (often used in combination with hubs)

- Containerised solutions

- Truck-drone combination

- Autonomous vehicles

- Delivery droids

- Crowd sourced delivery

- Parcel lockers

- Cargo-hitching (combining passenger and freight transport)

Source: European Alternative Fuels Observatory, 2022

This diversity offers significant flexibility for fleet managers, but it also makes the decision-making process more complex. To solve this challenge, Bpost has adapted its vehicle choice to various location typologies in the city. The operator uses e-trailers and small e-vans in inner cities, a combination of small & medium vans in second zones, and bigger vans in the third zone. The priority is to electrify the inner cities first. Bpost does a regular assessment of its operations to understand which vehicles are most suitable for which specific area, in collaboration with its workers’ union. This allows the company to reorganise its operations and foster a continuous dialogue with its members of staff.

Financing

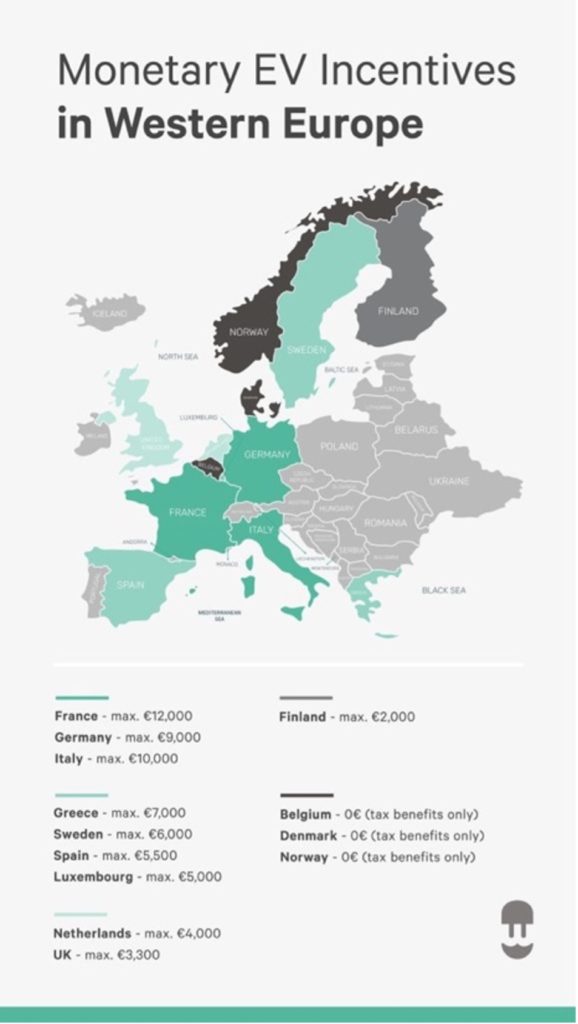

While prices for EVs have gone down in the recent years, purchasing an entire fleet to replace old Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicles can be a major financial effort. A comparison of the total cost of ownership (TCO) for small, medium, and large vans (realised by Breikers) shows that depending on size, TCO can vary for Diesel cars, EVs charged on public sites, or EVs charged on own premises. In the Dutch model, the charging strategy has the biggest cost implications, with on-site charging helping to reduce TCO by approximately 15%. The situation might be different in other countries, depending on taxes, benefits, and cost of electricity. Nonetheless, most European countries are currently offering fiscal support for the uptake of electric vehicles in the form of tax benefits or purchase incentives (see ECLF for cycling schemes and ACEA’s overview for EVs in EU27 in 2021). Certainly, diversification poses a serious dilemma for fleet managers: choosing a one size fits all or a fit for purpose approach. The former is cheaper, but does not leave sufficient flexibility for changing demands, while the latter is more expensive and might not be covered by the fiscal support mechanisms mentioned above.

Route planning

Various factors are determining logistics companies to pay more attention to route planning: from traffic regulations (e.g., time zones, low emissions zones, etc.) to vehicle characteristics (e.g., smaller and electric vehicles might have more limited cargo capacity and range). Our interviewees have confirmed that most of the times, payload and range are not an issue, since most logistics operations (especially parcel & post) do not surpass approximately 100km/days. Nonetheless, charging infrastructure still poses an issue and is predicted to remain the main barrier at least for the next 5-10 years. Connected to this, range anxiety continues to affect drivers, especially when their delivery environment varies significantly from day to day and is less predictable. Furthermore, while route planning is easily available for cars and vans, it becomes significantly more problematic for cycle logistics since cities might not have a functional and updated cycling route planner (which should include loading and unloading zones, safe parking, etc.). Similarly, multimodal logistics remains difficult to plan and organise due to varying load capacity and different ranges. Nonetheless, as Bpost shows, different vehicle and technology combinations (e.g., e-trailer and cargo bike, caddy and walking) can complement each other and provide suitable solutions for decarbonised last mile logistics.

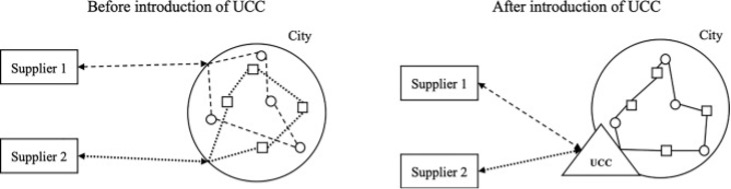

Organisation of hubs and urban consolidation centres

Route planning depends greatly on the availability of hubs and storage spaces. Finding suitable space can be a major challenge for fleet managers, as facilities in city centres might have high prices or simply be unavailable in dense urban cores. Besides, certain zoning regulations might prohibit the development of logistics (micro-)hubs, and residents might also oppose their development due to potential increase in traffic and congestion. Nonetheless, urban consolidation centres (UCCs) and logistics hubs are important to decrease the number of freight vehicles and their mileage in urban areas. Postal carriers, who already have a dense network of facilities around cities, might have fewer issues in securing space, although some zoning regulations might also prevent them from changing the use of space.

Charging infrastructure

Electric and hybrid vehicles depend on the availability of charging infrastructure, whether it is public, semi-public or private. As seen before, the charging infrastructure affects both route planning and the total cost of ownership, influencing the drivers’ acceptance of fleet electrification. Although fast charging options are available in many cities, the cost can be difficult to predict as prices vary widely. Thus, fleet managers need to devise a charging strategy considering the trip planned, the availability and cost of charging infrastructure. Our interviews suggest that fleet managers should seek professional help in this regard, as charging is a highly strategic and complex issue. Electric cargo bikes are less problematic in this sense, as they operate with interchangeable batteries.

Recruitment & training of staff

Many service providers are having difficulties with finding technically skilled personnel, as older persons are reaching retirement age, while younger ones tend to continue their university studies and seem less attracted by vocational education (AUAS, 2021). Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic has induced a shortage of heavy goods vehicles drivers, and it could be followed by van drivers due to the high pressure of the job combined with its loneliness. Besides labour market shortages, fleet managers must also ensure the continuous retraining of existing staff, to keep up with operational changes. Investment in lifelong learning is not only needed for accomplishing new tasks, but also to facilitate the transition towards different practices and reduce reluctance to change.

Bpost represents a positive example, offering training for each new type of vehicle tested. The company acknowledges that there might be different mentalities across the areas where they operate, and try to adapt their strategy as much as possible. To overcome any reluctance or anxiety caused by diversification, Bpost involves its employees in the choice of vehicles and routes, while emphasising that this positive culture change is happening within the entire company and beyond it, too.

Customer services

The type of customer served has a big influence on the fleet management strategy. Decisions should be made according to the location of the customer, their preferred delivery option, and willingness to support sustainable operations despite potential higher costs. For example, car-free zones stimulate the use of cargo bikes and parcel lockers, whereas rural areas could potentially be served by truck-drone combinations. Fleet managers that combine a range of customers will face strategic decisions towards the fleet strategy of different customer segments.

Solutions and innovations

At least three important solution pathways can be identified, coming from the stakeholders in the traditional quadruple helix: governments and public bodies, higher education and research & technology organisations, logistics operators/industrial suppliers, and the civil society. Although many of these will be initiated by governments and public bodies (either proactively or reactively), the success of most solutions will depend on multi-stakeholder collaborations. These pathways are focused around setting Sustainable Urban Logistics Plans (SULPs), providing fleet acquisition incentives, and developing & testing of new logistics models and equipment advances.

SULP developments

Moving towards the ‘near zero emission urban logistics by 2030’, the EU is strongly supporting the development of SULPs. More and more cities are developing or updating their logistic plans, which in turn gives a baseline for logistic operators to develop their logistics models and accompanying fleets. Often, SULPs give an indication of other measures and policies that might be affecting logistics operators, such as Zero Emissions Zones (ZEZ), loading and unloading areas, etc. Moreover, when cities develop their SULPs together with all relevant stakeholders, operators and cities alike may be able to come to mutually beneficial solutions.

E-Fleet acquisition incentives

The second pathway, which is government-led, includes tax reductions and purchase incentives for electric freight vehicles. Since the transition from an ICE fleet to an electric fleet can be costly, these incentives are a relevant measure to increase EV uptake. Almost every EU Member state has adopted some form of e-fleet acquisition incentives, with the majority of incentives constituting tax benefits. It should be noted, however, that there are large differences in the size of incentives on both national and regional levels.

Development and testing of equipment and logistics models innovations

Through this pathway, more knowledge and market-ready solutions are created for logistics operators and local authorities. Three examples of promising solutions for city logistics include containerisation, cargo bikes and e-LCVs.

Containerisation

Like maritime freight transport in the mid 20th century, urban freight transport could benefit from containerisation. In essence, containerisation eases the transfer of goods from one transport mode onto another. At the borders of the inner zone of cities, containers could be easily placed by larger vehicles and subsequently emptied by last-mile delivery vehicles. Different applications are emerging, ranging from autonomously driving container vehicles to stationary placement of containers, or last mile delivery vehicles that enable easy swappable containers.

e-LCV & Cargo Bikes

As shown in figure 1, e-LCVs have been gaining momentum amongst European fleet managers. Moreover, automotive OEMs are making advances in their usability and cost. A promising example includes the vehicle developed under the URBANIZED project. The project aims to provide modular, easily swappable cargo bodies & flexible EMS for different applications. These measures are aimed at bringing down costs and increasing energy efficiency.

Like e-LCVs, cargo bikes are targeted for use in last-mile delivery. Additional advantages over e-LCVs include their ability to access car-free zones, lower energy usage and lower total cost of ownership. One thing worth mentioning is the high maintenance needs of cargo bikes and the need to train and convince staff to use them.

Key Takeaways

Fleet managers are currently facing a difficult puzzle, induced by increasing external pressure from customers and city policies. Augmented diversification of the last-mile delivery fleet could in theory deliver economic, safety, and environmental benefits. However, significant complexity arises from the uncertainty in city policies and a range of operational issues. Cooperation with both internal and external stakeholders is required to come to align with fleet compositions, logistic plans, and city policies. Here, the rise of novel fleet solutions, clarity in city planning and financial support could form solution pathways to fleet management issues. The coming years will likely show a period of change in city logistics, where different stakeholders are developing and testing different logistics models that eventually form the stable future of the eco-system.